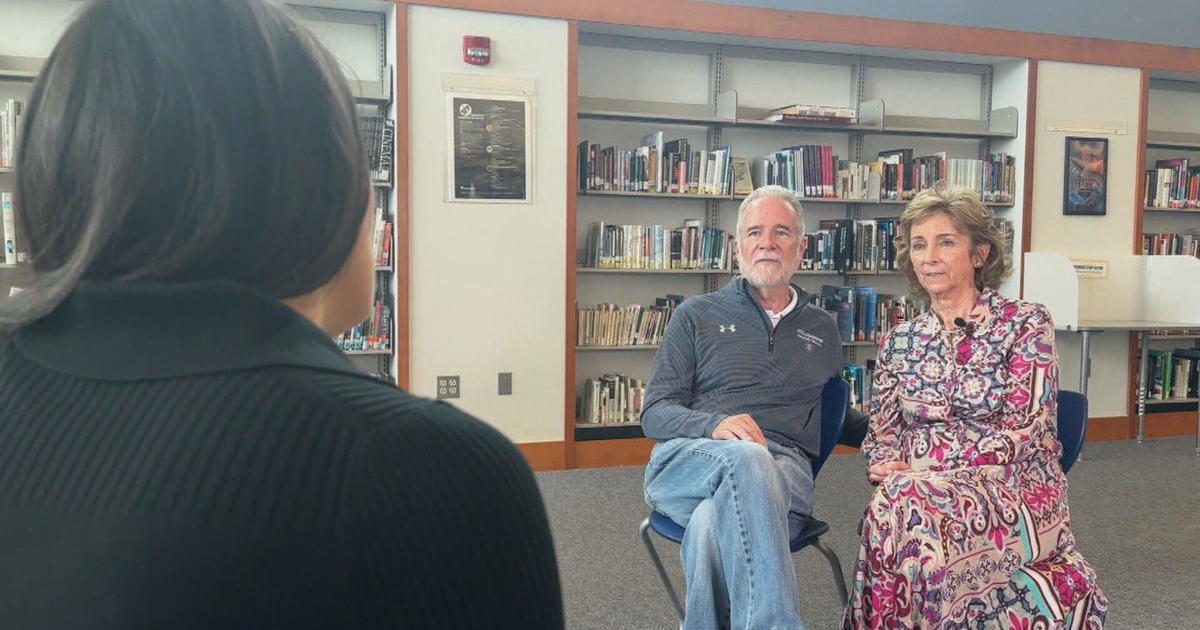

Colorado Researcher Offers Answers For Those With Vaccine Hesitancies

AURORA, Colo. (CBS4) - Researchers helping the COVID-19 vaccine become a reality as quickly as possible say that was their plan all along because it was essential to fighting this virus long after it had started a pandemic. They argue there are multiple factors unique to the response over the past year that allowed a safe and effective vaccine to arrive in less than a year.

"It in no way cut corners, it in no way decreased our ability to evaluate safety," said Dr. Thomas Campbell, the chief clinical research officer at UCHealth and the associate dean for clinical research at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "There was just overwhelming community support for these trials, such that there were many more people that came to us asking to join the trials than we had the capacity to enroll."

Campbell explained the process for developing this vaccine allowed them to tackle multiple steps in the trial at the same time. Instead of waiting for one step to finish, they started receiving data early enough to move to another step. Another major resource was the abundance of willing participants so the trials for all three vaccines could begin immediately.

"These are the first vaccines to come out and be implemented and rolled out using the mRNA technology. I would predict that they won't be the last," Campbell said.

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are the first to use this technology, but the investment and research into this approach dates back to the 1990s. Campbell says the type of immune response created by the vaccine is good for a virus like COVID-19, but may not work for other diseases. He does expect mRNA will be used for many other infectious diseases because this approach targets a single protein from the virus, called a spike protein. A method that has worked in the past, a vaccine for Hepatitis B targeted one protein in the 1980s, he explained.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses a viral vector approach, which is an older technology. All three vaccines are not considered "live vaccines" where a live, but disabled virus is given to the body to build immunity. This method was used for vaccines like small pox.

"The fact that there was so much COVID going on in this country, practically in the late fall, early winter, that allowed the trials to get the data that they needed to determine if the vaccines worked much faster than anyone thought would happen," Campbell added.

To test the effectiveness of any vaccine, people need to get sick from the disease in question. The worldwide pandemic created millions of cases, with most in the U.S., so the trials got the data needed sooner than expected. Campbell says they always needed to know quickly if the vaccine was working, which is why the factors at play were essential in moving the process forward when they saw it was effective.

"All of us should be very thankful that it happened very quickly, otherwise if we didn't have a vaccine, we have variant viruses that are emerging that are resistant to naturally acquired immunity," he said. "We would be in much different place right now as a society."

Another element to the research that helped develop a vaccine so quickly is the history with similar diseases. COVID-19 is just one of the coronaviruses the world has faced in this century. SARS-CoV-2 is the current virus we are fighting, but in the early 2000s, there was an outbreak of the first SARS-CoV, which likely came from bats as well. Severe acute respiratory syndrome or SARS was an epidemic that did not have the same public health challenges of COVID in this pandemic.

"Public health officials could identify who had it very quickly just based on symptoms and to isolate those individuals and quarantine so they couldn't then transmit it to others," Campbell said of other coronaviruses.

About a decade after SARS-CoV, there was MERS-CoV, or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. MERS-CoV also avoided the widespread infection we see with COVID, neither of the other two coronaviruses required a vaccine. The ability of this latest coronavirus to spread without someone showing major symptoms or appearing asymptomatic caused many more challenges.

"People don't know that they're sick or they're very mildly sick and yet they can still spread the virus," Campbell explained about COVID patients. "That makes it much more difficult to contain using public health measures."

Wearing a mask, social distancing, and isolating infected patients all helped contain SARS-CoV and MERS, experiences that helped health authorities react to the current virus. But because that was not enough for COVID, researchers had to look at those outbreaks to take the response one step further.

"A lot of the technology that went into making these vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 a success was learned from those two other coronaviruses," he said.

An effective plan accomplished the goal of delivering vaccines quickly to the public and the work done in the past year will help fight other infectious diseases in the future. While none of the vaccines are fully approved by the FDA, the emergency use authorization was necessary to get the vaccine out in time to make a difference during this pandemic. Campbell expects approval once more data is available on the vaccines.

In addition to the concern about the rushed process, he knows vaccine hesitancy also comes from skepticism among communities of color. He says some have worried that not enough people of various racial backgrounds were part of the trial.

For all three vaccines, almost 100,000 people participated with more than 36,000 Latinos enrolled and another 15,000 Black volunteers. Data available now shows the vaccine is just as effective on people of color as it is on white patients.

"We should all be very proud and thankful that we were able to do what we set out to do," Campbell said. "I think what we've learned from SARS-CoV-2 will be the playbook for the next pandemic."