Pipeline Dream: Ambitious Proposal To Bring Utah Water To Colorado

(CBS4) -- A Fort Collins man is pressing forward with a proposed 325-mile-long pipeline which would transfer water from northeastern Utah into the northern part of Colorado's Front Range. It could cost Aaron Million a billion and a half dollars to build.

He claims to have sufficient support from private investors to make his pipeline dream a reality.

"The reality is, Colorado needs an alternative water supply," Million said.

Nine years in, state and federal regulatory authorities have refused to give him clearance.

The latest setback came in November when the state of Utah rejected the idea again. A spokesperson for the Utah State Engineer, who refused to give the project approval, said the state office is waiting for Million's next move.

Million acknowledges that might be through attorneys and courts.

"The project's on track. This is just a process. We're moving forward on a variety of fronts."

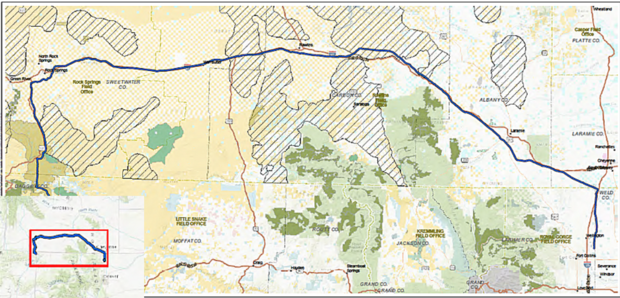

It's a process that started in the basement of the Colorado State University Library when the now-60 year old was studying for his Resource Economics degree. He found a 1913 map showing usable grades stretching from the Green River near Flaming Gorge Reservoir, north into Wyoming and then parallel to Interstate 80, extending into the Cheyenne area. By the time he found the map, most of that route was already established with pipeline delivering natural gas.

His idea was to use lay new pipe over the existing natural gas lines, thereby taking advantage of earlier permitting.

"We've been able to stand on the shoulders of previous work," Million said.

The rest of the concept: Pumps, solar- and wind-powered, as well as natural gas self-reciprocating engines, would push water uphill to Rock Springs. From there, electric power would be generated by in-line turbines as the water travels downhill.

A brand new section of pipeline from Cheyenne would bring the new water to an as-yet unestablished reservoir located somewhere north of Fort Collins, preferably close to the Rawhide power plant where the newly-generated electricity could be plugged straight into the power plant's transmission lines and distribution system.

Another branch of pipeline is tentatively planned to descend the Dale Creek drainage from Wyoming and dump more flow into the upper stretches of the Poudre River. That's an area that sorely needs it, said Million, who claims to be an avid fisherman and kayaker. More than half the year, the Poudre lacks any flow at all.

"There's not enough to fill a beer can" in the river in January, he said. His project would change that. "This will be a completely secure underground system that will be able to deliver 365 days a year. This will be a completely closed system."

Million made the concept the subject of his master's thesis in college, and he hasn't given up on the idea since. Work on it began in earnest in 2012. It's now called the Water Horse Project.

"No one has ever questioned the ability of water to move from Wyoming to Colorado, from Utah to Wyoming, from Utah to Colorado," Million told CBS4, citing legal precedent. "The right to move water from one upper basin state to another is absolute."

Current water providers aren't so sure, and are skeptical the project will ever pass the federal government's guidelines.

"I can't imagine how they're going to this through Wyoming and Utah," said Rep. Jeni Arndt (D-D53), Chair of the state legislature's Agriculture, Livestock & Water Committee. "I don't know how they're realistically going to get that done."

She also questioned whether Utah will decide to part with its own water knowing it would benefit Colorado citizens.

Million, who grew up on a ranch in Green River, Utah, and who knows the usage demands placed on the Colorado River (which the Green eventually flows into), said the numbers are on his side. His project aims to pull 55,000 acre/feet of water annually from the Green River, which has a total flow of 4.2 million acre/feet.

"This is one-half of one percent of the river," Million said. "This Green is a giant river with very little consumption use, very little compared to the Colorado. The Green has none of that. It's very flexible."

Million points out that the headwaters of the Green River originate near Jackson Hole, Wyoming. By adding runoff from those mountains to the Front Range supply, Colorado increases the "diversification of its water portfolio," he said.

"This helps differentiate our entire water supply. If you have one savings account and it gets depleted, you're S-O-L. But if you have also have a 401k..."

With that, Arndt agrees.

"I can see why people are trying to get more water here," she said, noting 80% of the state's water supply is on the Western Slope where only 20% of the population resides. "Aaron's talking about getting more of the resource."

She adds it's not that simple. Learning to reduce consumption has to be part of the long-term plan, too.

"We have a mismatch between the growing population and the supply. We need to conserve. We need to change how we live. We can't continue to have everything we have now."

Municipal water managers have the same worries.

"The City of Greeley is growing. We're projected to double in population by 2050," said Adam Jokerst, Deputy Director of Water Resources for the City of Greeley.

In an unusual move, Greeley's City Council is expected to approve in March the purchase of underground storage.

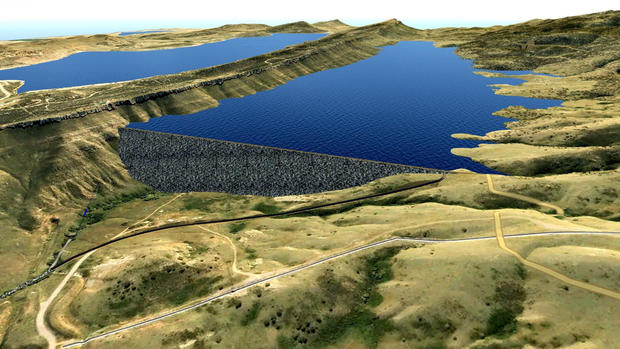

The Terry Ranch project will house a new supply of water under 10,000 acres of grassland near Carr, Colorado. Engineers have determined a natural aquifer exists there - one not currently supplied by any natural stream, river or lake but which promises to retain the same amount of water that would exist in a surface lake.

It will hold an estimated 1.2 million acre-feet of water - 48 times more than what the City of Greeley currently uses annually.

"It's really the capstone project for Greeley," Jokerst said. "It takes the place of a large surface reservoir that had a lot of environmental impacts. So we're really excited about that."

The Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, which manages the water supply for six municipalities, is working on two new reservoirs.

The first, Chimney Hollow Reservoir, will link up with nearby Carter Lake west of Loveland.

The second, more complex and controversial project is the Northern Integrated Supply Project (NISP). It involves two new reservoirs (Glade and Galeton) drawing from the Poudre and South Platte rivers, several pumping stations and miles of new pipeline.

"Many people move here from areas where water is a problem to be gotten rid of, rather than water is a problem that you don't have enough of," said NCWCD spokesman Jeff Stahla. "It's a reminder to those of us who might be newcomers to the state of Colorado that water's precious here. It reminds us that we live in a semi-arid portion of the country. We have enough of it to give us good beer and good agriculture, to live in great cities and have great farms, but we don't have any to waste."

Both agencies eye Aaron Million's concept with caution.

"Greeley's not opposed to the project," Greeley's Jokerst said.

"Our organization is dedicated to the projects we have in front of us," Northern Colorado's Stahla followed. "For others who are looking to fill some of the water supply gaps that might occur later this century...we're neutral on those sorts of things."

RELATED: Historic Colorado Wildfire Season Could Impact Drinking Water For Millions

That's not exactly a "welcome to the neighborhood."

There's a reason.

The most significant impact of the Water Horse Project, should it be approved, may come from the uninvited collision of ideals. Specifically, the principles of the past and the necessities of the future.

For the first time in our state's modern history, public resource might mix with private investment in the water world.

Previously, they've mixed as well as oil and water.

Colorado water law declared water a public resource in the 1860s as the State Constitution was being formed. Water rights were - and still are - granted to those who could prove their immediate use of it.

Water rights do not work like land ownership, for example. A water right cannot be purchased and held, unused, for appreciating value over time.

That activity is referred to by the water industry as "speculation," and for a century and a half, such profit-centered pursuits have been excluded from the development of the water supply.

RELATED: Construction Begins On Pipeline To Deliver Water To 40 Colorado Communities

Private development "must be balanced with the public interest," Jokerst said. "Water is the property of the state and of the citizens of the state. A water right just gives somebody the right to use it. I think it's very dangerous to allow too much speculation in water."

Doing so would increase prices that, without privatization, have already increased six-fold in the last decade.

"Early on," Stahla added, "the folks who developed the Colorado constitution and Colorado water law recognized that if you turn water into a straight economic commodity, that it really could do damage - that is unintended - to other industries like agriculture and to the tourism industry and to mining."

RELATED: Denver Water's Gross Reservoir Expansion Project Gets Final Federal Approval

A study enacted last year by the state legislature reaffirmed that stance. In fact, the study group asked for suggestions to strengthen it.

Million argued any privatization would actually bring the water business back closer to where it began.

"The private sector initiated the water development in this state," he said. "It's a public good, like a hospital, but it's held privately."

Both sides agree northern Colorado needs more water in the future. But changes to the current system may not happen soon.

"Knowing it's taken us 20 years to get a permit to build Glade Reservoir in Larimer County, building a reservoir is a complex task," Stahla said. "We've been working really hard to get a reservoir built, and we're getting really close. I'd say 'Godspeed' to anyone trying to get another reservoir built in northern Colorado."

Rep. Arndt agreed, calling Million's Water Horse Project a 20-year effort as well.

In that time, the Front Range communities will need to decide if it matters where the additional supply comes from, and whether a public agency or a corporation provides it, she said.

Values may change over time and under pressure.

"We will need to have a community conversation - which is a nice way of saying 'a political fight,' about how we change," Arndt said.