CU Boulder Professors: 'Tax' On Satellites Will Reduce Space Junk

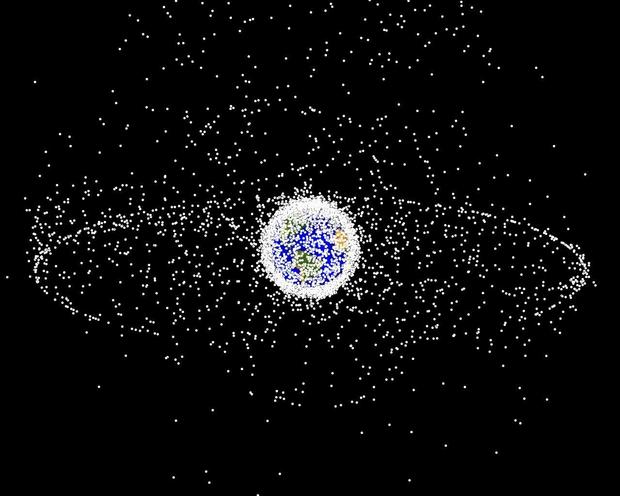

BOULDER, Colo. (CBS4) -- Just beyond the reach of Earth's atmosphere, an estimated 20,000 objects travel around the planet in low orbit. The objects are working satellites or non-functioning space debris -- old satellites and the remnants of the rockets that put all of them into place.

Farther out, in what's called a geosynchronous Earth orbit, are another 400-some objects.

As more objects are launched overhead, there are growing concerns about collisions among them.

RELATED: Dozens Of Lights Spotted Over Colorado Were SpaceX Starlink Satellites

A University of Colorado economist, Matthew Burgess, believes this additional risk should be offset by additional fees. These "orbital-use fees" would apply to every new satellite placed into orbit.

"We need a policy that lets satellite operators directly factor in the costs their launches impose on other operators," said Burgess.

Burgess co-authored a new study on the topic. It was published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He and the other researchers think the current solutions that involve mechanically removing the objects with nets, harpoons or lasers, or managing the de-orbiting of a satellite at the end of its use, don't adequately solve the problem.

The researchers said each operator launches more and more satellites until their private collision risk equals the value of the orbiting satellite. A better approach to the space debris problem, Rao and his colleagues found, is to implement an orbital-use fee—a tax on orbiting satellites.

"This is an incentive problem more than an engineering problem. What's key is getting the incentives right," said Akhil Rao, assistant professor of economics at Middlebury College and the paper's lead author. "Launch fees by themselves can't induce operators to deorbit their satellites when necessary, and it's not the launch but the orbiting satellite that causes the damage."

The charge for each satellite would be calculated to reflect the cost to the industry of putting another satellite into orbit, including projected current and future costs of additional collision risk and space debris production -- costs operators don't currently factor into their launches.

"In our model, what matters is that satellite operators are paying the cost of the collision risk imposed on other operators," said Daniel Kaffine, professor of economics and RASEI Fellow at the University of Colorado Boulder and co-author on the paper.

The researchers also claimed an international agreement to initiate orbital-use fees to about $235,000 per satellite would also increase the quadruple the value of the satellite industry by 2040, mainly in recouped costs of repairing or replacing collision-damaged satellites.

Burgess is an assistant professor in Environmental Studies, an affiliated faculty member in Economics at the University of Colorado Boulder, and CIRES Fellow. CIRES (Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences) is a partnership of NOAA (National Oceanagraphic and Atmospheric Administration) and the University of Colorado Boulder.