Hop Farms Popping Up Around Boulder County

BOULDER, Colo. (AP) - When the sold-out Great American Beer Festival kicked off this week in Denver, the carnival of craft beer will have a new competition category: Fresh Hop Ale.

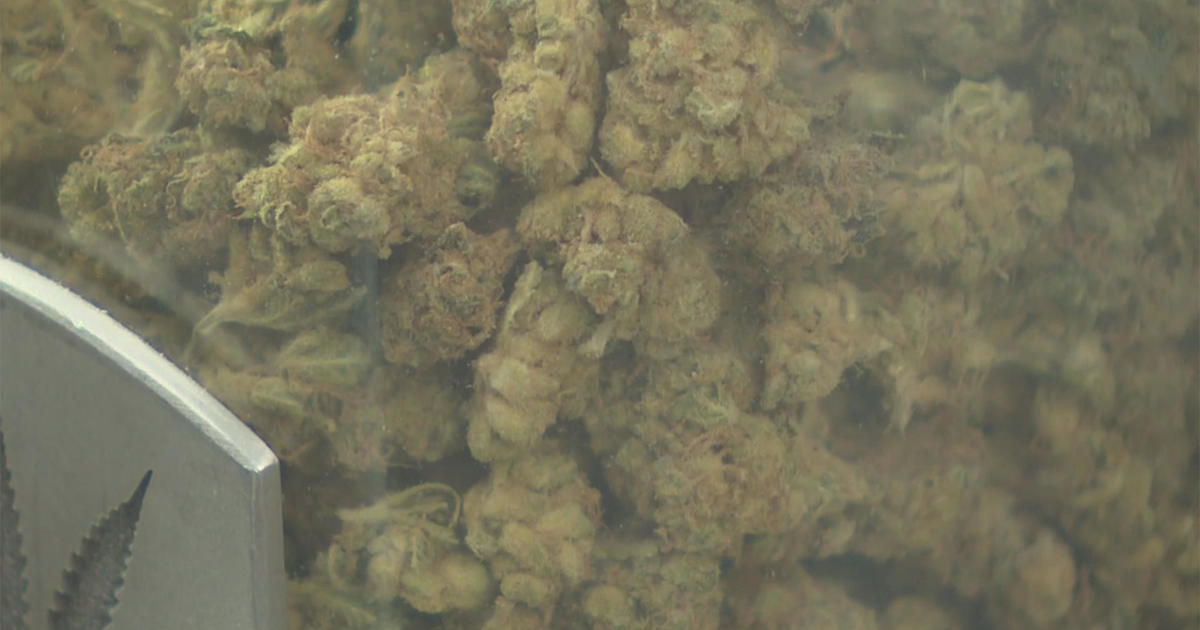

The category highlights the brewing technique of using fresh "wet" hops during the harvest season. Preliminary figures provided by the Brewers Association, the Boulder-based trade group that puts on the annual festival and competition, show that at least 33 brewers have entered the Fresh Hop Ale competition.

"The timing of the festival this year gave us an idea that we'd see more entries, and the confidence to break fresh hop ales out as a stand-alone category," Chris Swersey, GABF's competition manager, said in a statement. "In the future, this category might vary as a standalone or a subcategory of Experimental Beer, based on event timing and other trends."

While fresh-hopped beers are nothing new to the craft brewing industry or GABF - they previously were submitted to the Experimental Beer category - the growth of fresh-hopped beers poured by Boulder-area brew houses is a reflection of a budding trend in Boulder County and Colorado: the rise of hop farms.

During the past five years, at least three dedicated hop farms - Andrews Family Farm, Niwot Hops and Oskar Blues Hops and Heifers - have sprung up in Boulder County to serve the regional craft beer industry.

"Obviously it's difficult for them to provide us hops in the middle of February, but it's really a lot of fun in the summers," said Bob Baile, president of Boulder-based Twisted Pine Brewing Co., which trademarked the phrase "Farm to Foam" for its series of beers made from all-local ingredients.

Because of their size and financial barriers to accumulate the necessary infrastructure to dry and pelletize enough hops to meet a brewer's supply needs, the Boulder County farms primarily sell whole hop cones to brewers statewide. A good chunk of the activity has come during harvest time as they quickly shuttled fresh hops for craft brewers' specialty beers.

"(Commercial-scale) is way down the line for these guys, but I liken that to breweries starting out," Baile said, noting the slow progression from draft to bomber to bottling machines and six-pack carriers. "...They're trying to get a foot in the door."

In recent years, a couple dozen hop fields have come on-line across the state. The largest purchaser of Colorado's hops last year was AC Golden Brewing Co., which bought 90 percent of the state's yield - roughly 12,000 pounds - for use in its Colorado Native lager.

"So we made a conscious decision that even though we could buy hops from Yakima, Wash., for $4 a pound, we were willing to wildly overpay farmers in Colorado to grow these hops," Glenn Knippenberg, AC Golden's president, said in an emailed statement. "We wanted to way overpay so they could justify the infrastructure and create a hops industry in Colorado."

Totaling an estimated 150 acres, Colorado's hop farms are a drop in the bucket of the larger hop-growing hubs across the globe, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, central Europe and South America, where some single hop farms are nearly 2,000 acres in size.

As the state's craft beer business continues its boom, farmers and industry members say they expect beer-related agriculture to continue to ramp up in Colorado; however, the growth in the scale of individual farms might not come easy.

"Historically, before craft beers came into the picture, beer production was done on a large commercial scale," said Frank Stonaker, professor and coordinator of the Specialty Crops Program at Colorado State University. "The craft beer industry is looking for unique flavors and certainly the 'buy local' and organic ingredient portion of the equation is important to brewers as well as consumers.

"It's opened up areas all around the country for (hop growing). Certainly in Colorado, we have the highest density of microbreweries, so we have an advantage there."

Five years ago, farmer Rich Andrews decided to try a little experiment by erecting some trellises, installing an irrigation system and planting seven varieties of hops on a 1-acre patch of his 6.5-acre farm just north of Boulder.

Faring well were varieties such as Cascade and Chinook. Not so hot: Sterling, Golding, Centennial and Willamette.

"At that point we had no idea anybody was growing hops in Colorado at all," he said.

Andrews now supplies to brewers such as the Pumphouse in Longmont, the Wild Mountain Smokehouse and Brewery in Nederland, the Dillon Dam Brewery in Dillon and the startup Bootstrap Brewing in Niwot.

Bootstrap is entering a beer made from Andrews Family Farm's hops into the GABF's new Fresh Hop Ale category.

Andrews has taken what he's learned from his hop experiment and also his engineering savvy - he also crafted a picking machine and a solar-power hop dryer - and partnered with Colorado State University' Specialty Crops Program on its hop agriculture research.

He also has opened his doors to other farmers, hop growers and those interested to try their hand at the crop.

"I've been pretty much an open book in talking to anybody that's interested."

That included Will Witman, who started his half-acre Niwot Hops farm in Niwot three seasons ago.

As Niwot Hops just wrapped up its third year of production, co-owner Witman said he and business partner Lisa Dent are evaluating how best and how much to grow the operation.

"We have no trouble selling hops," he said. "Getting bigger ... that's to be decided. We have to find space; it would be a quantum leap to grow."

The current expectation is for Niwot Hops to remain a "sideline business," he said, adding that there are some planned adjustments - including growing some of the trellises by 4 feet - that could further increase the yield of Cascade, Chinook and Crystal hops for next season.

"We're obviously very small," he said. "To grow appreciably, there are problems that will have to be solved."

Growth goals for smaller growers such as Niwot Hops could be met through partnering with other farms on equipment, he said.

Neighboring hops farmer said the research and altruistic approaches could be vital in fueling further growth of a local industry that has high barriers to entry, Andrews said.

"It's certainly feasible in terms of the market that's there," he said. "...The problem is an economy of scale issue."

Andrews estimate the startup costs - not including labor - could range from $8,000 to $11,000 per acre. Once ready for harvest, the cones could be hand-picked, but that comes at greater costs, notably time. Throw in uncertainties regarding water and weather and the complicating factors grow.

The machinery to pick, dry, process, pelletize and bail the hops for greater commercial use are too costly for small growers, he said. Andrews estimates that 10 acres could be the minimum average plot needed for a commercial-scale operation.

"If somebody wants to be a hop grower, don't go into it blindly," he said. "... Because you could lose your shirt otherwise if you don't go in with your eyes open."

- By ALICIA WALLACE, The Daily Camera

(© Copyright 2012 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)