Drought Puts Baca County Residents On Edge

SPRINGFIELD, Colo. (AP) - There's nervous laughter when Baca County residents are talking about the drought.

There are serious issues brewing for Baca County if a large rain doesn't come soon.

"It's on everyone's mind," County Commission Chairman Troy Crane said. "It's as dry as I've seen it, although there have been areas of moisture."

The last steady rain was in August 2010, and there are broad consequences for a county that has seen more than its share of droughts. Agriculture will take the biggest hit, with 500,000 acres and thousands of cattle at risk. There have been nearly a dozen major fires, with a couple of homes destroyed.

After 80 years of dealing with droughts, the residents of Baca County are accustomed to nature's feast or famine. Soil conservation has improved with better farming techniques since the Dust Bowl when massive black clouds of dirt regularly swept over the area. Drought persists and has caused problems for the county every other year or so since 2002.

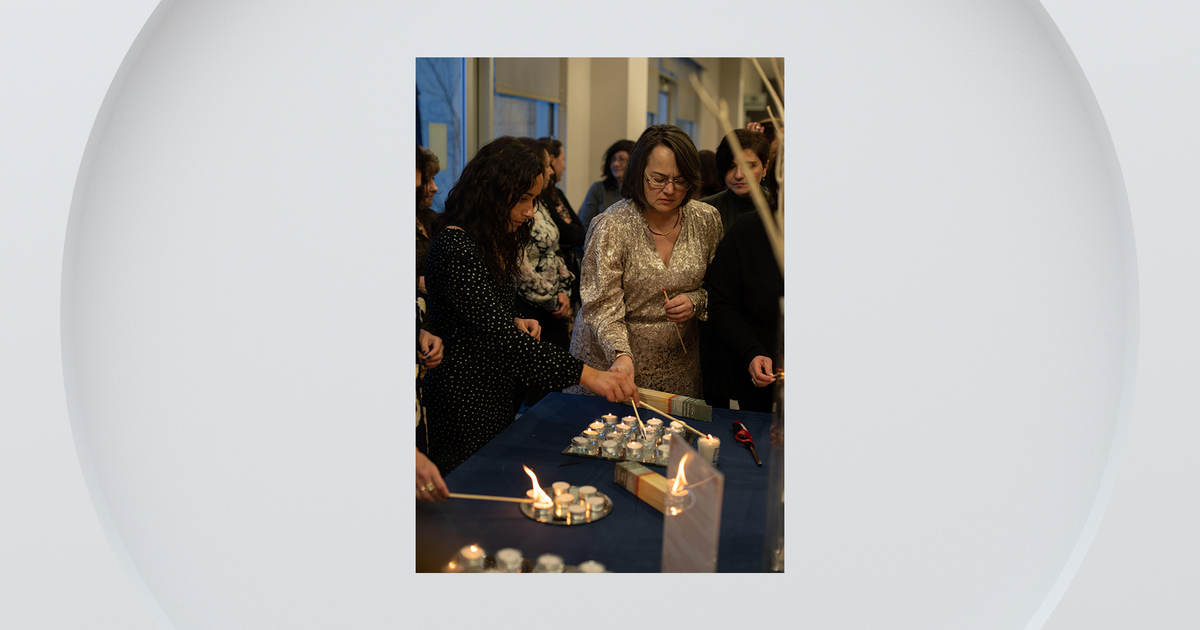

People are hopeful, however. They talk about getting the one big rain that could make or break a corn crop in the next few weeks. They're eyeing conservation reserve ground to tide the cattle through. An Easter Sunday community prayer service in Walsh thanked the firefighters and prayed for rain."

A farmer eating lunch at Campo recently put the dilemma everyone faces succinctly: He had invested $60,000 in fertilizer on his dryland corn fields earlier this year and had $20,000 in corn seed ready to plant.

"Unless we get a good rain, I won't plant," he said.

The window of opportunity for planting corn is closing. The door is just about to blow shut on wheat, said Brent Fillmore, head of the local Farm Service Agency.

"Typically, we run about 250,000 acres of planted wheat," Fillmore said. "It goes in by October."

Last year produced a bumper crop of wheat. Soil moisture was good and rainfall near the average of 15 inches for Baca County.

"Everyone was hopeful. We had excellent conditions for last year's crop. Rains came at just the right time. You couldn't have asked for anything better," Fillmore said. "This year, it's just the opposite."

This year wheat covered by wells -- about a quarter of the farm ground in Baca County is irrigated -- is doing all right. Even some of the dry land has sprouted because of the rare, isolated rain.

But it should be knee-high by now, and the fields are starting to look stressed.

Planting for corn, the next largest crop at about 150,000 acres, should be starting now, but farmers are holding back because of the weather. Later, about 80,000 acres of sunflowers and 40,000 acres of milo usually would be planted.

"Without any moisture, those won't do well, either," Fillmore said.

Most farmers carry insurance, but the payments vary from farm to farm.

The cattle herds -- culled already during the 2002 drought and the blizzards of 2006-07 -- are threatened, with some ranchers already talking about reduction. There are more than 50,000 head in the county.

One of the consequences of drought could be to close federal grazing leases on the Comanche grasslands, which will be evaluated according to the conditions on a case-by-case basis. The county commissioners are studying whether to ask for disaster relief, which could open Conservation Reserve Program ground to grazing.

As of last week, there had been at least 10 serious fires that threatened property in Baca County. That's fairly early in the season, and without rain the worst may be yet to come.

"Mainly, they've been electrical fires," said Sheriff Dave Campbell. "Some caught quick. The thing is, we're just coming into the dry lightning season. You know it's bad when you start getting scared of your storms."

Joe Rosengrants, 76, still helps his sons with farming, but his "hobby" is Sand Arroyo Energy, which markets wind turbines and solar panels. He decided he couldn't beat the sun and wind, so joined them.

While excavating the site of a wind charger recently, he found no sub-moisture 3 to 5 feet deep, where it normally would be encountered.

"I don't know if I've ever seen it any drier. It's not as nasty as I've seen, but the farming methods have improved so much," Rosengrants said. "We used to have storms where you couldn't even see the hood ornament on your car, back when cars had hood ornaments."

Farmers in Baca County are largely using no-till or low-till methods that reduce the possibility that the soil will blow away.

Baca County from 1935-38 was at the center of the worst soil erosion of the Dust Bowl era. It had been homesteaded when the railroad came in and by the 1920s had a peak population of about 12,000. Today, just 3,780 people live in the county.

There was still a major problem with blowing dust until the early 1960s.

In the sandy area south of Springfield where the Rosengrantses farm, it wasn't uncommon to plant a crop three or four times when the primary method was to plow out fields. New techniques and better equipment -- more expensive equipment -- have reduced erosion. Those who have stayed in are better farmers, he said.

"It was mostly subsistence farming, now everyone's big. You either got big or you got out," Rosengrants said.

Another major improvement came with high-production irrigation wells in the 1960s.

"Most the wells are in the Ogallala Aquifer, which is dropping by about 2 feet per year," said Commissioner Peter Dawson. It's expensive to drill deeper, so some wells have been abandoned or farmers make do with less. "A well that was pumping 800 gallons per minute 30 years ago, might be just 150 to 200 gpm today. On the other hand, irrigation practices have improved so much."

At first, furrow irrigation was widely used, but more have switched to center pivots, with heads that drop closer to the ground. Some farmers are using drip irrigation.

But even those who irrigate need the rain. There are no major rivers to deliver the water, so farmers look to the sky.

"I have 2,400 acres of wheat, and it's just sitting there waiting for a rain," said Shaugn Thompson, 37, who returned to the Walsh area to farm after graduating from the industrial technology program at Fort Hays State in Kansas in 1996. "I'm worrying about all of it."

The irrigated acreage -- about one-third of his ground -- will help him make it through the year, but it's not enough. Thompson had great production in 2009-10, but now there's no subsoil moisture to draw from.

"Corn has to have rain. Irrigation just can't keep up down here," he said. "We need rain today, or at least in the next two weeks. It's going backward pretty fast."

A public prayer might not hurt.

In 2008, 100 people showed up at a similar service to pray for rain. Shortly thereafter, it began to rain again.

"A few weeks later we had a public celebration," Matzke said.

- By Chris Woodka, The Pueblo Chieftain

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)